by Leidy V. González

Published on February 13, 2019

At 6 PM, when there are no more classes, after-school programs, and it was time to go home, I was out on the streets. I needed a way to stay alive, so I forged bus passes to board buses every night. Even though I was doing something wrong, I never felt guilty. It felt righteous to sleep on the bus. It was somewhere to rest my agonies and sorrows, weep, and survive every night. Writing letters to momma kept me going, but the 720 bus was my lifeline. It took me to school or connected me to homeless shelters. It was always there for me when I had no other options.

In high school, I never told anyone my mother was sent to prison and after my father kicked me out of the house for being queer, I became homeless and lost control of my life.

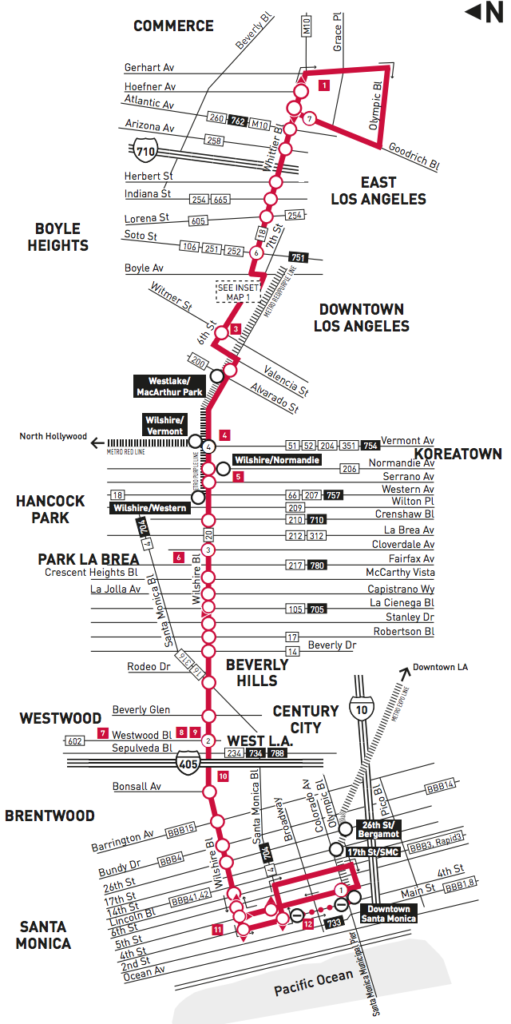

Bus Line 720 Route in Los Angeles.

Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority, 2018.

One evening, the pain from starvation and menstrual cramps took over. I decided to get off the bus and shoplifted for food and menstrual products. I never got back on the 720 that night. Instead of sitting in the back of the bus, I was sitting in the back of a police officer’s car. Arrested for shoplifting, my life crumbled in front of me. I tried to explain to the officers that I was homeless, hungry, and needed pads. They didn’t care. To them, I was just a criminal. I slept in a cell and and woke up to be released back in the streets.

There are hundreds of people risking their lives to cross the border, for a chance at a better life. Often, I thought that the odyssey to this country was the pinnacle of my struggles. Beyond how traumatic and depleting it was to arrive here, surviving in this country is an excursion of its own.

Once here, my struggles didn’t magically disappear. I never tell mom about the twist and turns I deal with while she’s in prison. Nothing happening to me measure up to her pain of being in a cage. She lost her freedom and her children, for simply trying provide for us, in a system set up for her to fail. My mother is one of many victims of the prison industrial complex. My mother turned to crime because the system that incarcerated her gave her no other choice. Her brown skin made her a felon. A woman, undocumented, and a hustler to support us — the police didn’t see her as my mother.

My mother’s absence, imprisonment, and severe sentencing, is what I call the “pain to prison pipeline,” a social structure that directly funnels women like my mother and me to a cell. Our deplorable living conditions and traumas incarcerated us.

I never wanted to end up in prison. I didn’t want to steal food or pads. I didn’t want to sleep on a bus or find shelters in Boyle Heights. I didn’t want to forge bus passes. If I didn’t do all that, I would probably not be writing this. At 27, I still ride the 720 bus every morning, but now, it’s to get to UCLA.

My journey is not a success story; it is a testament to the U.S. criminal justice system that caused it. It is a testament to the struggle of many people who seek shelter on buses because any other option is a crime. It is illegal to be poor in this country. Incarceration and homelessness is a revolving door of arrests and homelessness, influenced by the government. The government, though, isn’t punished for their crime.

Works Cited

- Davis, Angela Y. and Cassandra Shaylor. 2001. “Race, Gender, and the Prison Industrial Complex: California and Beyond.” Meridians 2(1): 1-25.

- Nichols, Laura and Fernando Cázares. 2011. “Homelessness and the Mobile Shelter System: Public Transportation as Shelter.” Journal of Social Policy 40, 333-350.

- Nelson, Laura J. “As waves of homeless descend onto trains, L.A. tries a new strategy: social workers on the subway.” Los Angeles Times, April 6, 2018.

***

Leidy V. González is all that remains after all her family and her roots were taken from her. She was born and raised until the age of 12 by her grandmothers in Bogotá, Colombia. She traveled 3,475 miles and crossed many borders to escape war, violence, and abuse. She is an undocumented body that has lost her ability to move but keeps walking, keeps riding her bicycle, keeps living. Leidy is the first in her family to finish middle school, high school, and to attend university. Her passion is to dismantle the criminal justice system that took her mother away for 7 years and deported her to unknown lands.

I appreciate the way I’m which you brought your story back around to the beginning to complete your message and tie all of your points together. In addition, the inclusion of the map helped give a visual aid to your nightly path of mobility so as a reader we can get a sense of the path you took and the spaces you transcended in your search for security. The other day in class we watched a video of the 24 hour line in Silicon Valley and through your story I feel I understand the implications of that video a bit more because I have now had a glimpse in through both the third party videographer and the first person narrative or someone who actively experienced it. To end, in situating your personal experience in terms of the prison industrial complex, the different layers of structural violence are revealed. Not only do they directly affect the person incarcerated, your mother, but they also take form for years to come and affect those through associatation; whether it be directly through relation or a type of shared experience.

Thank you for sharing a deep and personal story. Your story connected with a lot of what we discussed in our class recently- about public transportation as shelter as well as the unjust incarceration of immigrant women. When you said that “It is illegal to be poor in this country” I had to stop for a second because it made me realize how true that is and how many of us don’t see that. There are so many ways that the government and legal system work against those who are struggling to make ends meet. Instead of helping or understanding, they criminalize and actively seek out people who are poor. Your story revealed some of the ways that the legal system is unjust and flawed and stories like this are necessary to hear so that we may all become aware.

I was drawn to respond to your story because I think it highlights something that are not considered in the common conception of the immigrant experience. That is the interaction between an immigrant body and the prison industrial complex. I want to make sure not to reinforce the rhetoric of immigrant as criminal. My intention is to say that existence as an immigrant often puts people into situations where they are surveilled because they supposedly look like a “criminal” or where they must commit crimes for things that are essential to survival. On another note, people often don’t often realize how much is at stake for people who are immigrating to the U.S. in their interaction with the criminal justice system. I feIt think this was really apparent in the circumstances of your mother’s deportation. I really wish the U.S. would stop allowing prison time to act as a disqualification for citizenship, especially when the methods that are actively used already target marginalized communities such as those of people immigrating. Someone’s identity should not become a disqualifier.

Thank you for sharing such a personal story, this really hit home for me. I agree with your statement, “It is illegal to be poor in this country.”. I feel that our society has set up such high expectations that are beyond reality. In order to get a stable well-paying job, we have to go through school. Nowadays, the value of a bachelor’s degree has declined. With job offers asking for more experience or a graduate’s degree. The increasing of housing has left a tremendous amount of stress for everyone, including newly grads. Post grad life consists of paying student loans so, how are we supposed to pay off our loans, get a good paying job, all while having a secured housing. Homelessness is a big issue that is often never brought up. It is not a housing, but a money problem. The government are the ones to be blamed for the increasing numbers of homelessness.

Thank you. Thank you for sharing this. Thank you for writing a personal story that allows one to reflect upon their life. Your story made me realized all the luxuries that are often–that I have– taken for granted, such as shelter, food, and peace. What resonated the most was the introduction. We never realize the things we need to do in order to survive. Surviving in this country is an unconscious act. The government sets lower-class citizens up for failure, without any regards to their well-being. The images that were displayed in my mind brought tears to my eyes. The idea of people who are there to “protect and serve” are heartless, emotionless, and unthoughtful. I certainly agree with your stance, “it is illegal to be poor in this country.” Homelessness is an issue that is often hidden and many are unaware of how large the homelessness population is. In response to government relations, the government are the ones to blame. If citizens of the country were their priority perhaps homelessness numbers and crime would decrease. I am proud you have succumb this journey and on the path to great success. Once again, thank you for enlightening me.

I agree that it’s illegal to be poor, homeless, and undocumented. This arrangement isn’t just unfair. It also maintains social structure and contract that assures those already well-off continue to thrive. The laws and regulations of this country almost guarantee poor people who are arrested will remaining in the criminal system. To be free, is to spend great sums of money in exchange for good lawyers and make bail. Homelessness and living on the street is criminal as loitering via sleeping and public indecency arises when businesses only permit paying customers restroom accommodations. Furthermore, an undocumented status makes one’s mere existence criminal and to be frank one’s immigration status arbitrarily delegates working, residence, and legal rights. Whether legal or undocumented, people pay into the system to survive but it unjustly favors those already well-off.

First of all, I want to say thank you for this story. What really kept drawing my eyes to this story, out of all the others on the site, was the picture you chose to headline your story. A bus route. Specifically for a bus in Los Angeles, this is familiar to me. Comforting, even. When I was in high school, I took the bus home from school most days. My mom usually got off of work at 5, and it took her 45 minutes to get me from school on a good day. Soccer or volleyball practice, or robotics club after school meetings would around 5 or 5:30, and mom usually wouldn’t arrive until 6:30 if she left work on time. Dad didn’t even get off of work until around 7. I could go to the public library down the street if I wanted, but they closed early on Fridays and sometimes I just wanted to be at home. When I had extra quarters, I could even take the 115 and the 102 instead of just walking to the 102 stop. So I thought the bus was always a convenient way to get home. I never thought of it as one. This story hit so close to home, not really because of physical location, but because of its familiarity. My experiences and yours couldn’t have been more different, but I still feel a connection to what you are saying. Jarringly, the parallels are as stark as the differences. So easily it could’ve been my story, but when I was travelling that route I was completely oblivious to stories like yours that probably were happening all around me. Thank you, again, for your story.

Thank you for sharing your story. It is stories like yours that open my eyes to the countless injustices happening around us. I was born and raised in Los Angeles County. I am aware of the drastic contrasts between the haves and the have nots in my city. I often commute to UCLA from Whittier, CA. Thus, I see how the environment shifts from one part of the city to another from police brutality to gentrification. Moreover, I understand how power shifts from citizens in white neighborhoods to the police in minority neighborhoods. Regarding homelessness, I often consider Starbucks a place for shelter. Routinely, I study at Starbucks starting around 6 am, and I regularly see similar faces. I smile and greet the regular patrons with their strollers full of their belongings. Through my interactions, these homeless people tend to stay until closing hours. As a result, the space temporally provides a place for warmth and sanitation.

it is through such a small number of words that you convey such immense emotion that ignites such an intense fire to whomever reads your story. I first want to say thank you for allowing others to read your words, as I believe it is a privilege to be able to gain insight on the lives of others through their own subjective experiences. And while this story is entirely your own, it sheds light on issues that so many folks have to experience on a daily basis, especially this branding of the immigrant as a criminal, “her brown skin made her a felon,” “the police didn’t see her as a mother.” I do believe that the prison industrial complex is structured in order to be maintained, rather than attempting to be dismantled. In other words, our structure wants bodies in prison rather than not. There needs to be the elimination of the conflation of legality and morality. And your story proves that.

I appreciate the choice of diction and the descriptive factors that were used in telling this story. The word choice made the images come alive in my mind. I felt like I was a passenger on the 720 bus watching your story unfold before my eyes. The vivid descriptions, in essence, not only helped me picture the story but brought me along your journey. Although I was born in the United States and have, in some form, always had a roof over my head I related immensely with the idea that “surviving in this country is an excursion of its own.” As a Black queer woman who grew up in poverty and relates all too well to the struggle to afford something as simple as menstrual products, many aspects of your story are uncannily familiar.

Thank you so much for sharing your story. What I loved the most was your refusal to decouple your trauma from the political systems that caused it. The line “my journey is not a success story; it is a testament to the U.S. criminal justice system that caused it” affirmed that your journey to UCLA should serve not as a heartwarming tale of hope, but as a bitter reminder and call to action to end queerphobia, police brutality, the criminalization of poverty, and the carceral state. It is so necessary and valuable to learn the narratives of women impacted by homelessness and incarceration because they are unfortunately far too often eclipsed by those of men. Reading the specific struggles you faced as a menstruating woman, from painful period cramps to needing to shoplift for menstrual pads to the police officers’ complete lack of sympathy to your circumstances, was absolutely infuriating. Your mother’s story was also deeply impactful; it is rare to hear about how the prison industrial complex functions as a system of reproductive injustice by removing mothers’ rights to their own children for years at a time. I love how you centered the 720 bus in your story and ended with how you still take it; although in a different context and for different reasons, it continued to be a part of your life. I have taken the 720 bus myself to interviews and for summer jobs, and it never would have occurred to me how a public space that seemed like such a mundane part of our day may have served as a lifeline to others.

Your story has opened my eyes to public transportation. I always thought that it had one purpose, to get to a destination. Now I realize that it is a destination. I’ve heard people complain about riding the bus and who they have to share it with. They don’t realize that everyone has different circumstances in which they are forced to choose the unfavorable options that are given. One can argue that they are still mobile because they can walk or ride a bus to a destination, but this mobility isn’t their own. It’s the mobility that was given to them by a higher power. In this case, the government strips individual power mobility, and gives them a false sense of mobility. They are forced to take safety in a bus. It’s not because they want to, but they risk their lives if they stay on the street.