By Phumeena Balasuberamaniam

Published on December 23, 2015

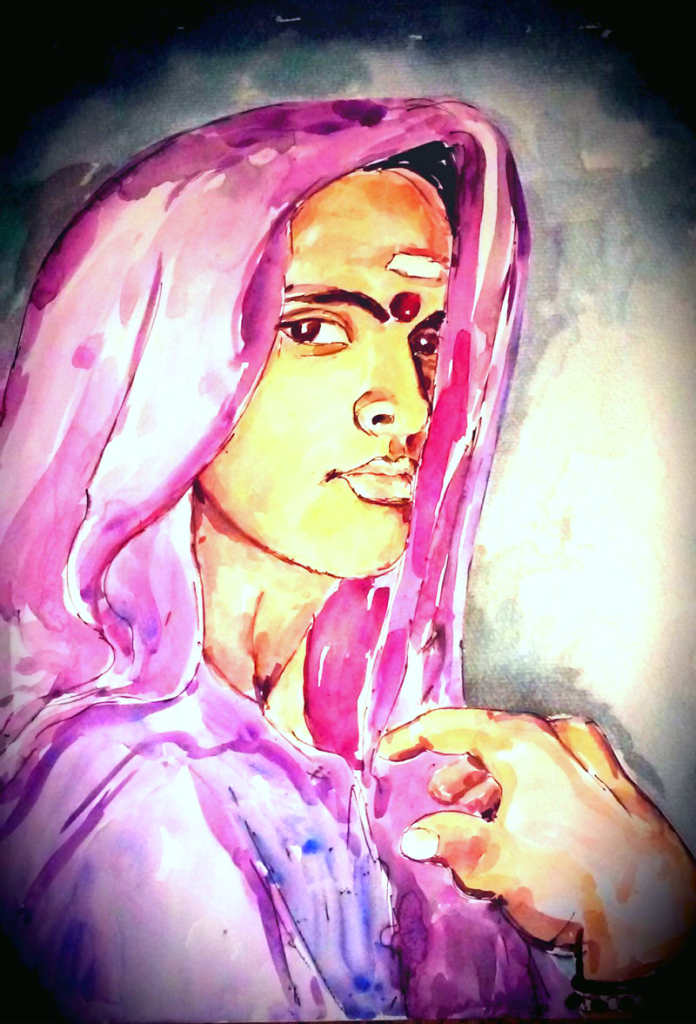

[caption id="attachment_1244" align="aligncenter" width="600"] “Untitled” by Phumeena Balasuberamaniam. Watercolor on hot press watercolor paper. 2015.[/caption]

The majestic lion, the pride of Sri Lanka

even its roar was unheard

as the animosity of the seething fire

refused to be extinguished

by the cries of the many innocents

it burnt alive

consuming lives

widowing newly-weds

orphaning young children

Escaping midnight bombings,

rape and murder

my parents fled

hiding with their three-month-old child

in a stranger’s

hot and filthy

car trunk

slowly

diminishing of oxygen

they left behind everything

the rich green grasslands in which they spent hours playing blindfolded hide and seek

the movie theater they sneaked off to, while skipping school

the library, where they met

but most importantly their voice

By air

By land

By water

they traveled

landing on the shores of Tamilnadu, India

“the land of Tamils”

a place of same ethnicity and ideology

or so they thought

Refugee status

discrimination

acceptance

years

all passed

Struggles never-ending

financial instability inescapable

led to

immigration to another soil

with promising futures

Canada

The quest for home

now eternal

this time,

in the eyes of a newborn Balasuberamaniam

Me

[caption id="attachment_1243" align="aligncenter" width="500"]

“Untitled” by Phumeena Balasuberamaniam. Watercolor on hot press watercolor paper. 2015.[/caption]

The majestic lion, the pride of Sri Lanka

even its roar was unheard

as the animosity of the seething fire

refused to be extinguished

by the cries of the many innocents

it burnt alive

consuming lives

widowing newly-weds

orphaning young children

Escaping midnight bombings,

rape and murder

my parents fled

hiding with their three-month-old child

in a stranger’s

hot and filthy

car trunk

slowly

diminishing of oxygen

they left behind everything

the rich green grasslands in which they spent hours playing blindfolded hide and seek

the movie theater they sneaked off to, while skipping school

the library, where they met

but most importantly their voice

By air

By land

By water

they traveled

landing on the shores of Tamilnadu, India

“the land of Tamils”

a place of same ethnicity and ideology

or so they thought

Refugee status

discrimination

acceptance

years

all passed

Struggles never-ending

financial instability inescapable

led to

immigration to another soil

with promising futures

Canada

The quest for home

now eternal

this time,

in the eyes of a newborn Balasuberamaniam

Me

[caption id="attachment_1243" align="aligncenter" width="500"] “Untitled” by Balakankatharan Ramavariar. Watercolor on hot press watercolor paper. 2015.[/caption]

Walking around the periphery of the Madurai Mariamman Temple, one of the many stops in my parents’ spiritual itinerary of 25 temples across the South Indian terrain, I was overwhelmed by the amount of unfamiliar senses. There was contrast everywhere, from the grandeur of the temple lit with thousands of tiny oil-lamps to the dark slum-like periphery brimming with panhandlers and young children begging local vendors for water. I was unable to hear beyond the continuously ringing temple bells and the persistent loud horns of automobiles nearby, bombarded by the repugnant smells of sweat and sewage mixed with the freshness of the jasmine in the hairs of the women walking in front of me. I felt suffocated and out of place. Making sure to avoid making eye contact with the panhandlers, who I was told would behave aggressively, I tried desperately to stay close to my family as the swarm of temple goers thrusted us forward.

Amidst the chaos, I was abruptly pulled next to my aunt. A pathway was suddenly cleared in the congested alleyway. Time seemed to stand still, and I became hypersensitive to my surroundings as the older woman who had just pushed past my cousin stood idle to let a group of women move through the crowd. I noticed their distinctive Tamil accents as well as their elaborate attire and flamboyant adornments and I saw a mixture of shock and disgust on the faces of the temple goers. Within seconds after they passed by, the crowd returned to its original bustle. My aunt and I quickly made our way to our taxi, and the encounter left my mind spinning with curiosity. Who were these women, and why did the locals react so scornfully to them?

The group of women I saw that night were Thirunangais, the transgender women of Tamilnadu, commonly known as the third sex. Thirunangais have a long history in India, having been represented in countless ancient texts as bearers of good fortune and even derivatives of Lord Ardhanareeswara, an androgynous form of Lord Shiva and Goddess Parvathi who are still worshiped in India. Having seen increasing portrayal of transgender activism in South Indian media, such as the work of the Sahodari Foundation founded by the transgender rights activist and journalist Kalki Subramaniam to provide community support for Thirunangais and fight for transgender welfare in Tamilnadu, I thought prior to this encounter that Thirunangais must have attained at least some respect and dignity, if not equality, within South Indian society. I learned, however, that accusations of theft, harassment for money, and prostitution continue to be associated with Thirunangais, and that Thirunangais continue to be stigmatized, ostracized, and shunned.

Although the people I saw did not hesitate to point their fingers at Thirunangais for turning to prostitution and panhandling for a living, no one could provide me with a convincing answer as to why they had to resort to it in the first place. The reality was that ignorance and callousness were pervasive among people who would rather disown their transgender children than counter the stigma and the shame associated with being transgender. Thirunangais were consequently not only often deprived of family support, but also had limited access to equality, education, employment, financial stability, and even healthcare — all of which I thought were basic human rights. Yet as I recall, I didn’t perceive hostility or insecurity among any of the Thirunangais I came across during that trip. Instead, I saw a sense of community and belonging in their eyes in spite of the fearful and disgusted remarks they received from others.

[caption id="attachment_1242" align="aligncenter" width="400"]

“Untitled” by Balakankatharan Ramavariar. Watercolor on hot press watercolor paper. 2015.[/caption]

Walking around the periphery of the Madurai Mariamman Temple, one of the many stops in my parents’ spiritual itinerary of 25 temples across the South Indian terrain, I was overwhelmed by the amount of unfamiliar senses. There was contrast everywhere, from the grandeur of the temple lit with thousands of tiny oil-lamps to the dark slum-like periphery brimming with panhandlers and young children begging local vendors for water. I was unable to hear beyond the continuously ringing temple bells and the persistent loud horns of automobiles nearby, bombarded by the repugnant smells of sweat and sewage mixed with the freshness of the jasmine in the hairs of the women walking in front of me. I felt suffocated and out of place. Making sure to avoid making eye contact with the panhandlers, who I was told would behave aggressively, I tried desperately to stay close to my family as the swarm of temple goers thrusted us forward.

Amidst the chaos, I was abruptly pulled next to my aunt. A pathway was suddenly cleared in the congested alleyway. Time seemed to stand still, and I became hypersensitive to my surroundings as the older woman who had just pushed past my cousin stood idle to let a group of women move through the crowd. I noticed their distinctive Tamil accents as well as their elaborate attire and flamboyant adornments and I saw a mixture of shock and disgust on the faces of the temple goers. Within seconds after they passed by, the crowd returned to its original bustle. My aunt and I quickly made our way to our taxi, and the encounter left my mind spinning with curiosity. Who were these women, and why did the locals react so scornfully to them?

The group of women I saw that night were Thirunangais, the transgender women of Tamilnadu, commonly known as the third sex. Thirunangais have a long history in India, having been represented in countless ancient texts as bearers of good fortune and even derivatives of Lord Ardhanareeswara, an androgynous form of Lord Shiva and Goddess Parvathi who are still worshiped in India. Having seen increasing portrayal of transgender activism in South Indian media, such as the work of the Sahodari Foundation founded by the transgender rights activist and journalist Kalki Subramaniam to provide community support for Thirunangais and fight for transgender welfare in Tamilnadu, I thought prior to this encounter that Thirunangais must have attained at least some respect and dignity, if not equality, within South Indian society. I learned, however, that accusations of theft, harassment for money, and prostitution continue to be associated with Thirunangais, and that Thirunangais continue to be stigmatized, ostracized, and shunned.

Although the people I saw did not hesitate to point their fingers at Thirunangais for turning to prostitution and panhandling for a living, no one could provide me with a convincing answer as to why they had to resort to it in the first place. The reality was that ignorance and callousness were pervasive among people who would rather disown their transgender children than counter the stigma and the shame associated with being transgender. Thirunangais were consequently not only often deprived of family support, but also had limited access to equality, education, employment, financial stability, and even healthcare — all of which I thought were basic human rights. Yet as I recall, I didn’t perceive hostility or insecurity among any of the Thirunangais I came across during that trip. Instead, I saw a sense of community and belonging in their eyes in spite of the fearful and disgusted remarks they received from others.

[caption id="attachment_1242" align="aligncenter" width="400"] “Untitled” by Phumeena Balasuberamaniam. Watercolor on hot press watercolor paper. 2015.[/caption]

Travailing through the mix of emotions and unpleasant realizations, I have come to be aware that my naive trip to India had become more than just a recreational activity. It’s questionable whether I would remember roaming the streets of Chennai, taking pictures of the city’s landmarks, or shopping for authentic Indian handicrafts ten years from now. However, I will remember the personal struggles I had in coming to terms with why such a significant social issue remained unrecognized and brushed aside in the mainstream Tamilnadu society. Discerning these struggles made my trip an enlightening journey, and even though I became puzzled and appalled, my queries helped me come to terms with my own quest for home.

The more I learned about the Thirunangai communities, or gharanas, the more I learned about their struggle against social stigma and discrimination and their quest for dignity and belonging. I have learned that a sense of belonging is not attained simply by sharing nationality, religion, race, language, or social hierarchies, but rather from the relations of solidarity in recognizing and fighting for a common purpose. It was due to this solidarity that Thirunangais from various social backgrounds are able to come together and build a community, providing each other with emotional and economic support. It was due to the lack of this solidarity that I myself had felt out of place in Tamilnadu, India, a land filled with what I once thought were my people. Defining my home based on its geographical location would be equivalent to accepting it to be a battleground where never-ending battles are fought over social structures, norms, and hierarchies. For me, home is not simply a nation or a locality as I had previously thought. Rather, home is a mindset through which one finds community, comfort, and security.

“Untitled” by Phumeena Balasuberamaniam. Watercolor on hot press watercolor paper. 2015.[/caption]

Travailing through the mix of emotions and unpleasant realizations, I have come to be aware that my naive trip to India had become more than just a recreational activity. It’s questionable whether I would remember roaming the streets of Chennai, taking pictures of the city’s landmarks, or shopping for authentic Indian handicrafts ten years from now. However, I will remember the personal struggles I had in coming to terms with why such a significant social issue remained unrecognized and brushed aside in the mainstream Tamilnadu society. Discerning these struggles made my trip an enlightening journey, and even though I became puzzled and appalled, my queries helped me come to terms with my own quest for home.

The more I learned about the Thirunangai communities, or gharanas, the more I learned about their struggle against social stigma and discrimination and their quest for dignity and belonging. I have learned that a sense of belonging is not attained simply by sharing nationality, religion, race, language, or social hierarchies, but rather from the relations of solidarity in recognizing and fighting for a common purpose. It was due to this solidarity that Thirunangais from various social backgrounds are able to come together and build a community, providing each other with emotional and economic support. It was due to the lack of this solidarity that I myself had felt out of place in Tamilnadu, India, a land filled with what I once thought were my people. Defining my home based on its geographical location would be equivalent to accepting it to be a battleground where never-ending battles are fought over social structures, norms, and hierarchies. For me, home is not simply a nation or a locality as I had previously thought. Rather, home is a mindset through which one finds community, comfort, and security.

Works Cited

- Agoramoorthy, Govindasamy, and Minna J. Hsu. 2014. “Living on the Societal Edge: India’s Transgender Realities.” Journal of Religion and Health 54 (4): 1451–59.

- Gagné, Patricia, and Richard Tewksbury. 1998. “Conformity Pressures and Gender Resistance Among Transgendered Individuals.” Social Problems 45 (1): 81–101.

- Gupta, Monisha Das. 1997. “‘What is Indian about you?’ A Gendered, Transnational Approach to Ethnicity.” Gender & Society 11 (5): 572–96.

- Michelraj, M. 2015. “Historical Evolution of Transgender Community in India.” Indian Streams Research Journal 5 (7): 1–4.

- Nagel, Joane. 1994. “Constructing Ethnicity: Creating and Recreating Ethnic Identity and Culture.” Social Problems 41 (1): 152–76.

- Reddy, Gayatri. 2005. With Respect to Sex : Negotiating Hijra Identity in South India. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Regi, Amal A., and Esther S. Rani. 2012. “Social Isolation of Eunuchs and Illegal Practices.” Indian Social Science Journal 1 (1): 11–24.

- Semmalar, Gee Imaan. 2014. “Unpacking Solidarities of the Oppressed: Notes on Trans Struggles in India.” WSQ: Women’s Studies Quarterly 42 (3): 286–91.

- Tambiah, Stanley Jeyaraja. 1991. Sri Lanka: Ethnic Fratricide and the Dismantling of Democracy. London: The University of Chicago Press.

Phumeena Balasuberamaniam is an avid doodler, incurable perfectionist, aspiring Carnatic musician trying to find her voice, and an inquisitive explorer who loves getting lost. Although her quest for self-identity as a Canadian-born Tamil ignited Phumeena’s passion for travel, it remains fuelled by a desire to understand the variety of cultural practices and injustices experienced throughout the world. In addition to her social engagements, travels, and devotion to the arts, Phumeena strives to discern life through her passion for biology, and is currently pursuing a specialist in Molecular Biology and Biotechnology at the University of Toronto Scarborough.

]]>

Phumeena Balasuberamaniam is an avid doodler, incurable perfectionist, aspiring Carnatic musician trying to find her voice, and an inquisitive explorer who loves getting lost. Although her quest for self-identity as a Canadian-born Tamil ignited Phumeena’s passion for travel, it remains fuelled by a desire to understand the variety of cultural practices and injustices experienced throughout the world. In addition to her social engagements, travels, and devotion to the arts, Phumeena strives to discern life through her passion for biology, and is currently pursuing a specialist in Molecular Biology and Biotechnology at the University of Toronto Scarborough.

]]>