By Pam Gwen

Published on January 30, 2019

“Para po!”

I hop off the jeepney and enter a Korean BBQ restaurant. I spot my relative’s faces, crinkling with laughter. Empty beer pitchers and sizzling meat scatter the table. After dinner, we plop into the car.

I blast Angel Olsen’s “Woman” on my iPod and fall asleep.

♫ “I’ve been thinking

How your smile seems to last forever

Even if it’s just a while

We are there together” ♫

Moments after, I hear whispering, “Tara, lawen tamu. Intrigued nakuman. Matudtud neman, paburen mu [Come on, let’s look. I’m intrigued. She’s asleep anyway, don’t worry].”

I don’t tell them I’m awake. I peek out the window and see the neon luminescence of Walking Street bars, casinos, and hotels. For the first time in months since I left Los Angeles, I see white Americans walking around—intoxicated older men, groping and kissing young Filipina women dressed in revealing clothing and high platform heels.

I hear my cousin say, “Banta milub la keng bar bayaran mulamung 2,500 pesos, yabe ne ing sex kanita [People can get in the bars, and they only pay $47 including the sex.]”

He steers away from the blazing lights and through a dark alley announces, “This is Santos Street, but it is really known as Blow Road. People who don’t have a lot of money go here. It’s probably around 600 pesos ($17) for oral sex.”

Out the window I see a Filipina woman naked and kneeling in the dirt — making her 600 pesos. My heart is pounding. I stifle the hitch of my breath and glue my eyes shut. Oh please let this be a bad dream.

***

Why did I look away? Why was I so adamant to distance myself from the Filipina bodies I saw? Did I think their sex work was a disgrace, that the women should have just gone to school and worked harder at something else?

At 21, I recognize the Filipina body as a persistent bridge between the colonial period and present day of the Philippines. The Spanish colonized the Philippines for 300+ years since 1565. In pre-Spanish Philippines, the native cultures had an egalitarian society with babaylanes, shamans or healers, as their religious leaders. Babaylanes were women or men in drag with power in the cultural, religious, and social lives of Filipinos. When the Spanish brought Catholicism, they reshaped the Philippines’ political economy and marginalized the women. Catholicism brought Virgin Mary as the submissive servant of God and the feminine symbol of sacrifice and passivity.

My family raised me with the beloved Virgin Mary and the purity and modesty that she stood for. My feeling of disgust towards the women was produced in combination with the American model minority myth that instilled values of assimilation, hard work, education, and individualism.

Why was I disgusted at the men? The men got on an airplane to experience Filipina women at their destination. Did they feel powerful?

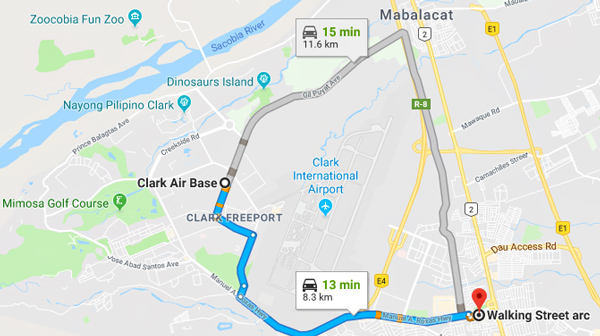

In 1898, the US colonized the Philippines after defeating Spain in the Spanish-American war. The arrival of the US during World War II meant the arrival of many military bases and American soldiers, the proliferation of the sex trade industry, and the representation of Filipina women as subservient, impoverished, and sexually available. One of those military bases was Clark Air Base in Angeles City, a mere 13-minute drive to Walking Street, where I was that night in 2014.

Sex tourism today is a $6 billion industry and the country’s most lucrative tourist attraction. “It’s More Fun in the Philippines” is a well-known slogan launched in 2012 by the tourism industry, but I think it’s more complex in the Philippines.

Sex trade seemed to be a simple matter of choice to me at 17, but narratives of former sex workers near the US military bases suggests otherwise. Lacking education, skills, financially sustainable employment, and meaningful socioeconomic mobility- sex work for many women was the only option available for themselves and their families.

I didn’t choose to visit Walking Street. I was an unwitting and unwilling voyeur. Confused and troubled by what I glimpsed, I buried the memory for many years. But my eyes are wide open now.

The Spanish left and the American soldiers withdrew from the military bases, but I see the ongoing composition of their traces still marching in the Philippines: religious conservatism and militarism, heteropatriarchal nationalism and racism, converging on Filipina bodies.

Works Cited

- “Santos Street (Blow Road), The Facts.” 2010. Asian Escapades.

- “Prostitution Revenue By Country.” 2019. Havocscope.

- Ahmed, Sara. 2000. “Recognising Strangers.” In Strange Encounters: Embodied Others in Post-Coloniality, 19-33. London: Routledge.

- Anderson, Jon. 2015. “Introduction.” In Understanding Cultural Geography: Places and Traces, 1-13. New York: Routledge.

- Chapman, Lora. 2017. “Just Being Real: A Post-Colonial Critique on Amerasian Engagement in Central Luzon’s Sex Industry.” Asian Journal of Women’s Studies, 23:2, 224-242.

- Sturdevant, Saundra Pollock and Brenda Stoltzfus. 1993. Let the Good Times Roll: Prostitution and the U.S. military in Asia, 1-343. New York: New Press.

- Zhou, Min and Yang Sao Xiong. 2005. “The Multifaceted American Experiences of the Children of Asian Immigrants: Lessons for Segmented Assimilation.” Ethnic and Racial Studies, 28(6), 1119-1152.

***

Pam Gwen takes each sunrise as an opportunity to practice gratitude and manifest her dreams. Pam grew up in the Philippines, Oklahoma, New York, and California. She is majoring in Gender Studies and minoring in Labor and Workplace Studies at University of California, Los Angeles. Pam is a UCLA community organizer and activist, outreach assistant for the UCLA LGBT Center, music journalist for UCLA Radio, marketing assistant for KCRW 89.9 FM, and a research assistant for the Department of Gender Studies at UCLA. Pam is most peaceful at sunsets by oceans, mountaintops in forests, and in her garden.

Pam Gwen takes each sunrise as an opportunity to practice gratitude and manifest her dreams. Pam grew up in the Philippines, Oklahoma, New York, and California. She is majoring in Gender Studies and minoring in Labor and Workplace Studies at University of California, Los Angeles. Pam is a UCLA community organizer and activist, outreach assistant for the UCLA LGBT Center, music journalist for UCLA Radio, marketing assistant for KCRW 89.9 FM, and a research assistant for the Department of Gender Studies at UCLA. Pam is most peaceful at sunsets by oceans, mountaintops in forests, and in her garden.

Hi Pam,

Thanks for sharing your story. I really appreciated the way that you discussed Filipina bodies as the bridge between the colonial and the contemporary. A lot of people ignore the ways that Americans influenced the economics and conditions that resulted in colonized female bodies being viewed/treated this way so I’m glad you pointed it out.

I also appreciated that you pointed out that Catholicism served as a catalyst that sparked the marginalization of women. This is true of so many colonies where Catholicism was forced upon natives. It’s very important to trace the reasons behind the disenfranchisement of women so we can best address it in the future.

As someone who loves history and is very interested in the women affected by structures of colonialism, I really enjoyed this piece. I like how you begin the story claiming you shut your eyes and look away from the Filipina woman but end it by saying your eyes are open to the colonial traces left in the Philippines. It is very symbolic from your shift of distancing yourself from the Filipina women to understanding what led to the decisions she makes and the conditions she faces. I also love how you bring yourself to the table in this discussion through explaining your thoughts on the Filipina woman as someone who was raised with certain religious beliefs under the American model minority myth. Your piece really resonates with me because it entails a cohesive understanding of how colonialism, religion, and heteropatriarchy, among other structures take place through Filipino women’s experiences and current lives in the Philippines and in your experience in America. You tie so many conversations in this story so well like a true history lesson.

I was raised in a place where the indigenous woman’s body has been misconstrued by American imperialism and capitalism, so I am able to find a lot of parallels between your story and what I have personally seen back home. By understanding how women of color operate under sexism, racism, and colonialism, I believe we are led to a narrative that shows the faults in the post WWII history that champions the West. Thank you for your story, Pam!

Hi, Pam

Thank you for sharing your story!

I really enjoyed reading your piece about the complexities of the lasting affects of imperialism and settler colonialism. American society choose to forget the harms soldiers cause in other countries because it is masked with their heroism and patriotism. As someone who has spent a lot of their life studying sex work and sex trafficking, I think its important for stories like these to be heard. We as individuals, or as outsiders can easily dismiss these women as disgraceful and ignore the structural institutions or lack of education or resources that have forced many women to par-take in sex work. I also resonated with your critique on Catholicism in relation to the piece because although I am not Catholic, I grew up in a neighborhood where everyone around were deeply rooted in the Catholic church. I first hand saw the affects the Catholic Church had on my female classmates in many ways, such as ensuring they remain pure and submissive.

Hey Pam,

Thank you for sharing this! It’s beautifully written. Given the villainization of sex work in many mainstream feminist movements, I especially appreciate how you compared your views towards sex work at 17 and 21. That way in which you narrated your growth highlights that we can unlearn problematic, knee-jerk reactions with a little contextualization. You did a great job deconstructing the inevitability of sex work at the convergence of gender, class, and race in the wake (or rather, continuation) of colonial forces. I also liked that you emphasized the ongoing legacies of colonization, as reflected in the violent heteropatriarchal, militarist structures present today.